What Digital Media ‘Gets Away’ With

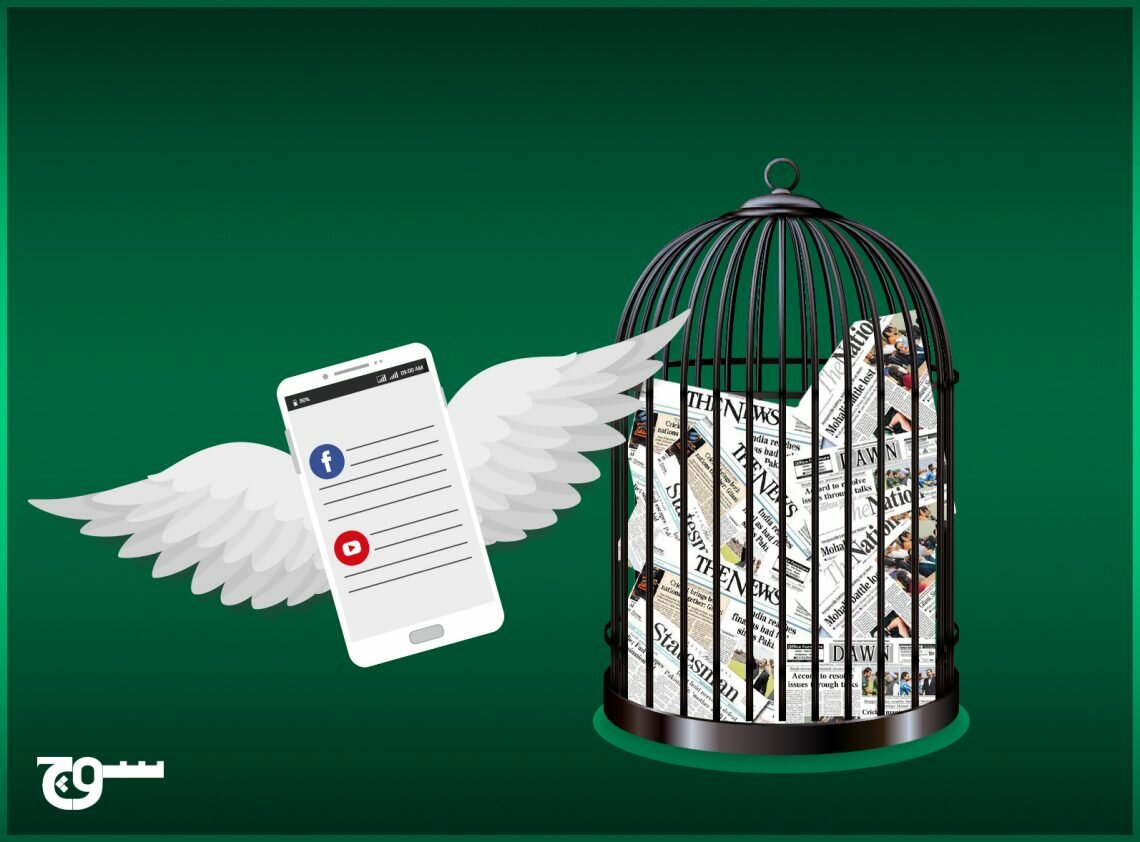

Whether its reports about aliens or sex, why is it that digital media appears keener to take risks than print media?

A few weeks ago, Talat Aslam, who has been editing The News’ pages for many years, found himself in an impromptu newsroom meeting; the discussion was about using the photograph of a swimmer on broadsheet. The swimmer, female, was photographed in a swimming pool, the only part of her body visible are her head and shoulders.

Aslam tells me they often have similar debates over using photos of tennis players. After all, in an industry where the likes of Orya Maqbool, TV anchor, can take issue with an advert that shows women playing cricket in formal kits, one can never be too careful.

The question the editorial staff were debating was: “Will someone mind [the photograph]?”

Invariably when we talk about media censorship, we refer to state censorship or censorship around discussing blasphemy law; these variants disallow you from challenging narratives around nationhood, the question of Balochistan, enforced disappearances, social movements such as the Okara Peasant Movement or the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), the hold of the army on Pakistan’s politics and economy and asking why a law built in the name of religion creates room for violence.

No one can deny that censorship around these issues demands priority; they are harming democracy and costing human lives. But, one can wonder if this is the only kind of censorship in the media?

Guessing the bounds of social censorship is just as tricky as with state censorship; because the lines are invisible, one never knows when they’ve been crossed. But a difference between state censorship and other variants is that while dealing with the former, you know who you’re up against. Your adversary’s mood and demands change from time to time, but at least it’s always the same entity. Within social censorship, you could offend anyone.

In my time in print media, more than once and at different media houses, it was the men running the printing press who were unhappy with a certain photograph, taking it upon themselves to darken or blacken an image they didn’t deem respectable for the paper. Signals can also come from page-makers (again, mostly men) who lay out pages after editors are done editing text, selecting texts and choosing headlines. I’ve also seen subtle warnings come from new sub editors, with a differing ideology, who have just joined the team. Aslam describes such people as “informal censors”.

Respectability is an ambiguous concept, that could vary from editor to editor. Since no one is drawing exact lines around them, but the presence of a net is palpable, editors could develop gatekeeper attitudes. It then becomes up to them to decide what is respectable to publish, and what is too base, too pedestrian.

Respectability is an ambiguous concept, that could vary from editor to editor; they develop gatekeeper attitudes. It then becomes up to them to decide what is respectable to publish, and what is too base, too pedestrian.

However, things appear a little different in the world of digital media. Online, young news websites are publishing pieces on the benefits of sex education, the cons of early marriages, divorce being a woman’s right, mental health, and LGBTQ rights among other things that would make most print publishers squeamish.

Pakistan’s digital media landscape is complicated, much like digital media across the globe. Print newspapers upload stories from their broadsheets online, but also produce digital-only content; television channels act the same way, with sharing their regular transmission online, but of late some channels, and reporters have also taken to Facebook live videos, or pre-recorded Vlogs to disseminate information; and then there are platforms such as Mangobaaz or Parhlo, Cutacut or Propergaanda, and Naya Daur or Surkhian that only exist online. What differentiates these digital platforms in not just that they only exist on our screens, but also that they don’t rely on traditional means of funding.

If digital media platforms don’t solely rely on the government and brands for funding, and if their readership is constricted to online readers do they ‘get away’ with more? Do they face less censorship?

It’s complicated.

Cutacut and Images, for instance, both exclusively digital platforms have done articles on vaginismus, a medical condition around the vagina that makes sex painful for women. You’d be hard pressed to find such stories in print media. But this doesn’t mean that all is cheery for editors running these platforms. “Social censorship, which is tied in with commercial censorship is far more widespread and everyday than state censorship,” says Shayan Naveed, the editor of Cutacut. “Simply put, we may have more liberty than traditional print media, but there is a still a lot that we don’t get away with.”

Sarmad Amer, the editorial director, for Mangobaaz, agrees with Naveed: “There is so much we don’t get away with.” Out of the many incidences of backlash he cites to me, one involves Mangobaaz publishing an article about a lesbian that resulted in a Change.org petition against Mangobaaz. They also received a message from one of their brands after this story was published, to make sure that in the future their content is more ‘family friendly’.

A more recent article of theirs that was poorly received was about a recent research which concluded that men’s beards carry more germs than dog’s skin and fur. “The backlash was overwhelming. In the comments section, people weren’t debating or discussing the story, there was only one opinion, they were all offended,” says Amer. Mangobaaz felt forced to edit the story after first publishing it, soften it at its edges, make it more palpable to the public.

It’s easy to regard Mangobaaz, a self-identified infotainment website, as vacuous. If you lean right, you could critique them for “importing the Western agenda”; from the opposite of the spectrum, you could say that they are commercializing issues without taking a stance; even centrists could express concern about how the website is leading to the buzzfeed-isation of Pakistani media and cashing in on clicks rather than ideology. What’s more complicated is to examine what Mangobaaz, and other digital media platforms, are bringing to the table, the ways in which they are pushing the envelope on the types of topics Pakistanis find respectable to report on.

This becomes especially true when you come across particularly bland digital platforms, that are doing nothing to push the boundaries. Maleeha Mengal, now an editor at Surkhiyan, an online news platform, began her career at one such website.

Before Surkhiyan, Mengal was working for the blogs section of a media house that also runs a TV channel. Although the blogs section was housed by the media house, it was not funded by them; they were self-sustained and yet the impositions on them were multi-fold. “We were told not to use the word ‘sex’ and to avoid the phrase ‘gender based’ in headlines,” as it would give readers the “wrong impression about what kind of website we were.”

We were told not to use the word ‘sex’ and to avoid the phrase ‘gender based’ in headlines,” as it would give readers the “wrong impression about what kind of website we were

Mengal relates an incident about how when an editor on the team wrote and published a fictional story about female sexuality, she was threatened by higher-ups with a legal show cause notice. “There was a whole scene in the newsroom with the director storming in and screaming,” she says. “They were angry that our website no longer looks ‘clean’”.

For Mengal, the problem was obvious. “We didn’t have journalists directing us, we had IT managers above us. And these managers were mostly men,” she says. She cites that print magazines such as EOS or The News on Sunday, get away with discussing as many socially important topics as most digital media sites. “But when you have a website run by IT directors, the focus will be on clicks, not content,” she concludes.

So to say that digital ‘gets away with it’ is unfair. It appears that like print, digital also has to maintain a delicate balance between publishing stories that ‘push social boundaries’ and taking care not to offend people’s sensibilities. The difference may just be that the bar for digital platforms for what goes, is set a tad bit higher.

Prominent mainstream journalists like Talat Hussain, Najam Sethi, and Matiullah Jan have also begun gravitating towards digital media. All three have set up YouTube channels under their own names, using the ethos they have built over the years as their own brand. Hussain and Jan’s channels are a rehash of what we’ve seen on TV before, them presenting a mix of opinions and facts about politics. Sethi seems to trying something different, for his own bit he has decided to stick to political analysis, but he is collaborating with a wide variety of mostly young journalists, writers, hosts, and analysts to make the channel about more than just politics.

Perhaps he realizes what his peers don’t? That the digital market, though much smaller, has a wider appetite. A vlog on Express News’s social media has a science journalist engaged in a sombre discussion about aliens, not the kind the former PM Nawaz Sharif claim cost him the 2018 election, nor the kind that are bereft of citizenship, but the ET variety. I’m willing to be corrected but apart from hastily put together TV packages from the 90s, I don’t remember being educated about the potential existence of aliens by Pakistani mainstream media. Whether its reports about aliens or sex, why is it that digital appears keener to take risks than print media?

Whether its reports about aliens or sex, why is it that digital media appears keener to take risks than print media?

There could be many answers. Some say it’s the fact that funding is coming from multiple sources, so digital feels that even if they offend one source, they have a back.

“The priorities, approach and language of digital-only platforms may appear different from those of traditional media, because they are focused on capturing a young audience,” says Asad Hashim, a reporter for Al Jazeera English. “So you may find them tackling stories that traditional media shy away from, particularly when it comes to culture and society.” Hashim says that another explanation could be that since “digital-only platforms are generally start-ups, in order to make themselves stand out from other publications, they pick up ‘controversial’ subjects, or tackle subjects in a controversial way, to gain traffic.”

Others say it’s about the editors, their own training, and the kind of mindset they have. “Most of print is run by old school, conservative journalists, who aren’t necessarily interested in taking risks,” adds Sabahat Zakariya, the deputy editor at The News on Sunday, a print publication that’s available online.

She also points out that social censorship does have a connect with state censorship. “Once they [the state] set the ball rolling, they create fear. Now editors and journalists are living in this state of never knowing what goes and what doesn’t,” says Zakariya.

An editor at an upcoming digital platform, who requested anonymity so as to not offend their publisher, explains that while working in print you internalize so much social censorship that even if you move to digital, as many journalists have, you feel “squeamish” about covering topics that aren’t considered respectable. “So, a lot of the social censorship editors face is self-imposed,” he says.

Still others say that the real reason digital takes risks and gets away with many of them is simply because who is even reading them? An advantage that digital platforms have, though they may not see it as an advantage, is their limited reach. When you write in English, you narrow down your readers, when you write in English and are only available online, you whittle your numbers down further.

“When I was editing for print, the stakes were much higher. There was a fear that one misleading word in a headline could lead to our office being burnt down. But now that I work for a small digital platform, no one even knows our physical location, I feel more confident about using words like sex, or periods, or even suicide, in headlines now,” says an editor who made the switch from print to digital last year. He also wishes to stay anonymous. In his case, it’s not the publishers he’s afraid of. But simply because “I’ve internalized so many nonsense fears during my years in the industry, I’m still trying to work through them,” he explains.

This might be the most worrying contradiction about digital media platforms: their sustainability is intertwined with their growth, but the moment they grow, they get on the radars of the state, the righteous and the moral police, and may find themselves against the exact same wall as print media. After all, YouTube was not shut across Pakistan because of the state or even the government, but because a group of ordinary, righteous Pakistanis felt they should decide what should be censored. With so much space already ceded to the state and to religious groups, who’s to say that in the next few years an offended morality brigade can’t organise on the streets.