Why is it so difficult to talk about female genital cutting in Pakistan?

Reticence, resistance and intimations of a reckoning

Content warning: detailed descriptions of procedures of female genital cutting

ON AN EARLYsummer afternoon in 1980, seven-year-old Leena Khandwala relaxed on the couch with her feet up, enjoying the onset of school holidays. She felt a rush of excitement when her mother asked her to accompany an aunt for shopping. The atmosphere was cheerful and relaxed, until it dawned upon her that this journey, and in fact this day, was headed in a different direction.

Walking hand-in-hand with her aunt, Leena was taken to a small apartment in Saddar, Karachi. The door was opened by a middle-aged woman with a stern expression on her face. The dimly-lit room was crammed with old furniture and smelt of traditional spices and fried food. There, Leena spent the next several minutes trying to decipher the huddled whispers of her aunt and the unknown woman.

As she struggled to understand, her aunt made her lie on the floor. The strange lady pulled out scissors, then pulled off Leena’s underwear. Suddenly, she felt a sharp cut between her legs, and pain shot up her body. Leena screamed, tears streaming down her cheeks. It ended as quickly as it began: she was wrapped in a big cloth diaper, then led out of the room.

Was she being punished for bad behaviour? Was there something wrong with her body? There was no way of knowing, because it was never mentioned again. She felt guilty and vulnerable. Urinating was agony: she was afraid to use the toilet for several days. Leena has one other memory from that day: as she was leaving that tiny Saddar flat, she was asked to kiss the hands of the hostess, the woman who cut her, as a gesture of respect. “It wasn’t easy.”

THREE DECADES LATER,Leena is an immigration attorney in New Jersey. It took her years to piece together an understanding of what had taken place that summer day: a form of genital cutting. “It was probably in my late teens,” she said, of her realisation. “I read, had conversations with friends and finally came to the conclusion that this was done to control my sexuality.”

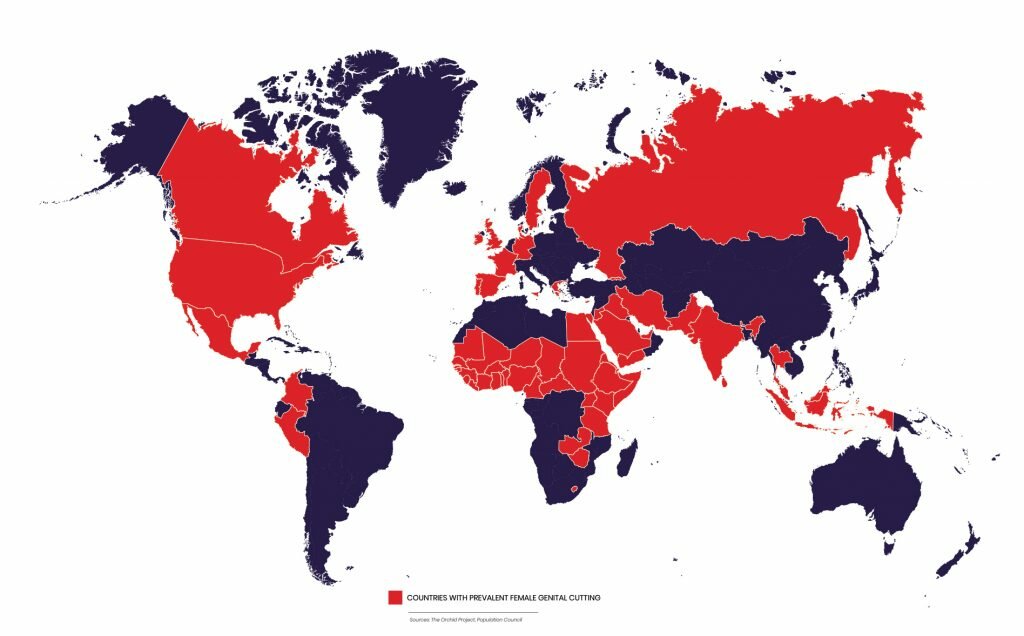

According to the United Nations, at least 200 million women in 30 countries have undergone genital cutting. Given the sensitive and stigmatised nature of the issue, however, it is likely these numbers do not reflect its actual scale. Gynaecologist Dr Azra Ahsan noted that medical literature has generally not listed Pakistan as an FGC-performing country. “The issue came to our attention very recently, when a medical team was editing a manual written in the West,” she said. “We asked doctors in the room if they’d ever examined patients with FGC. Most had not.”

“In 2011, the practice of female genital cutting in Pakistan was brought to the attention of a wider audience by local journalist Farahnaz Zahidi.”

In 2011, the practice of female genital cutting (FGC) in Pakistan was brought to the attention of a wider audience by local journalist Farahnaz Zahidi. She spent some time investigating the practice in Senegal—where advocacy and activism have drastically reduced the incidence of FGC, she says—and within the Pakistani Bohra community, where it is carried out on pre-pubescent girls between the ages of six and 12. “From what I have been told by [Bohra] community members, they do not perform FGC as invasively or aggressively as in other parts of the world.”

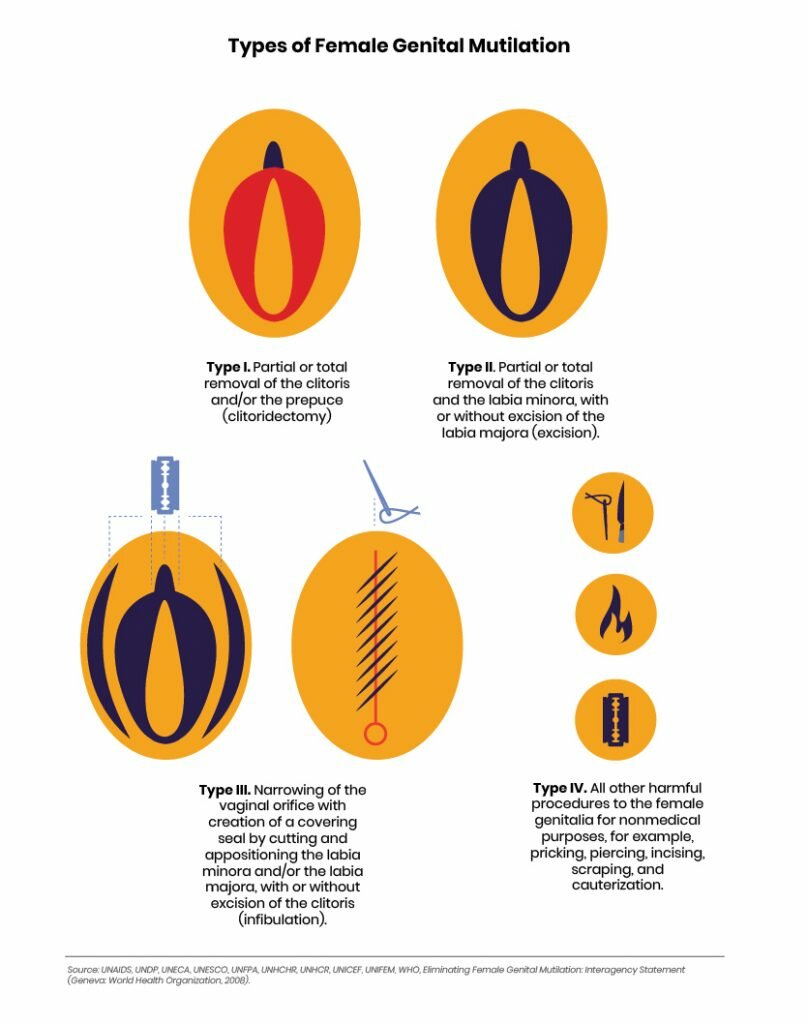

Since different communities around the world practice FGC with varying degrees of intensity, the practice has been grouped into four broad categories. In South Asian communities where this occurs, clitorodectomy (or Type I) is the most common: the removal of a pinch of skin from the clitoral hood or the clitoris itself. The most extreme form—infibulation or Type III—is mostly practiced in African countries and accounts for almost 10% of all female genital cutting. Here, the inner and/or outer labia are cut away and the remaining flesh from the outer labia is sewn together, leaving a small pea-sized hole for urination and menstrual flow.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) discourages all forms of female genital cutting, which it defines as ‘any modification to the female genitalia for cultural, religious, traditional or any other non-medical purposes.’ Globally, FGC violates well-established human rights principles—including equality, the right to life and the rights of the child—and international conventions against torture and cruel or inhumane treatment. In 2012, the UN General Assembly resolved to end FGC globally, and several countries introduced laws against the practice. Not so in Pakistan. Activists and lawyers say there are too many religious sensitivities and nuances on the types of genital cutting practiced in the country to impose legal bans here.

At its worst, female genital cutting can result in constant pain, difficulty having sex, incontinence, bleeding, cysts and abscesses, repeated infections—which can lead to infertility—and life-threatening complications during childbirth. Little data exists on the harmful effects of the least severe forms, such as those practised in Pakistan; available information on the medical complications of Type I genital cutting includes bleeding, pain, discomfort, a burning sensation, swelling and infection in the immediate aftermath of being cut. But Mariya Taher, cofounder of anti-FGC activist group Sahiyo, says new findings keep coming to light. For instance, she recently met a French surgeon who performs reconstructive surgeries on FGC survivors in the West.

“For Leena, the cut itself did not leave any obvious physical mark. Her scars are more psychological: fear of intimacy, anxiety and stress.”

Often, the damage is beyond what the naked eye can see. “When he opened up these women, there was a lot more damage inside,” she said. “There are several nerve endings that are damaged when the small piece of skin is cut, affecting physical health and sexual experience.”

Dr Ahsan herself has only recently started tending to patients who have undergone genital cutting. “I may have seen them earlier, but did not notice the cut because I was not sensitised,” she said. Since the cut is generally almost invisible, doctors will only spot it if they are looking for it.

For Leena, the cut itself did not leave any obvious physical mark. No medical practitioner or gynaecologist has ever remarked or expressed any concern while examining her. Her scars are more psychological: fear of intimacy, anxiety and stress. “Those feelings are a result of the deep trauma, not the cut,” she says. “They say a circumcised woman does not experience sexual difficulties but the truth is more complicated. Sometimes the trauma is so deeply ingrained that even the thought of intimacy is dreary. It is difficult to be scarred and feel completely at ease.”

IT IS DIFFICULTto pinpoint the roots of female genital cutting. Herodotus wrote about it in 500 BC as a practice among ancient Egyptians and scholars have reported evidence of cutting on mummies—possibly a sign of aristocratic distinction. But although many trace it to Africa, it is also practised among indigenous communities in Colombia that likely had no contact with the continent. In the 19th century, added Sahiyo’s Mariya Taher, clitoridectomies and female castration were reportedly performed in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (US) to ‘cure’ cases of “melancholia, masturbation, hysteria, lesbianism and nymphomania.” There are reports of female genital cutting being carried out for this purpose until the 1960s.

Some members of the Bohra community postulate that FGC was a way for their ancestors—especially merchants and traders—to ensure their wives did not have sex with anyone else while they were away. A version of this remains one of the primary rationales for genital cutting: to control women’s sexual urges. 47-year-old Sumaira* has had numerous arguments with her mother about this. “I think she feared I will get aroused and go astray. To prevent that, she got the ‘bug’ removed when I was just seven years old.” Women are trained to think they are “deviant” or “dirty” before they are even old enough to understand their own anatomy: “We grow up with warnings that sexuality, in general, is a fearful, violent thing.”

“I am unaware of how much my sexual experience has been altered by FGC due to the obvious fact that I was not sexually active at age seven.”

Rabiya*, 36, is a strong proponent of genital cutting. “I am an adult and an aware woman. By choice, I had it done to my 10-year-old daughter, and I do not regret it,” she asserted. “It’s the extra skin that is cut off. It gives control over ‘extra’ sexual urges. It doesn’t destroy you for life.”

There is no medical evidence to support this, nor Rabiya’s claim that there are health benefits to the practice. Thirty-year-old Fatima*, who opposes the practice, did however draw a comparison with male circumcision, arguing that it is also an elective procedure that removes ‘extra skin’—foreskin. In her view, the difference in acceptance of male and female circumcision practices is because of “the orientalist lens” on the issue. Male circumcision is a “Judeo-Christian sanctioned procedure”; female genital cutting does not have similar sanction, she argued, which is why it is looked down upon and labelled ‘mutilation’.

Male circumcision, however—mandatory for Jews and most Muslims but not Christians—is said to have limited health benefits: easier hygiene and decreased risk of penile cancer, urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted infections. But it can also result in reduced sensitivity and potential complications from procedure, though rare, may offset potential benefits. Routine circumcision of baby boys also violates the principle of consent to treatment. The American Academy of Pediatrics says benefits outweigh risks but lets parents decide. Still, Fatima’s response was telling: it betrayed anxieties within the community about how it was perceived by outsiders. Twenty-seven-year-old Zahra* voiced similar frustrations:

“This is the biggest misconception people have about us. It is not a compulsion. If you want to follow it, you can. Nothing in our community is forced. People make a big deal about it—those are the people not close enough to the community to understand why it is still carried out. Or maybe they are not part of the community itself.”

Rabiya worries that cutting has been deemed unethical because it is done at an age when the child cannot give consent. “I spoke to my daughter ahead of time and made it very clear to her. She was pretty much okay with it—she was scared but she knew what was coming. She will never stop trusting me, or blame me in the future,” she said. (Legally, however, a child cannot give consent.)

Rabiya’s defence of female genital cutting stems partly from her view of it as her religious obligation. According to Sumaira, there is a diversity of community opinion on the matter, with some declaring the practice obligatory, others arguing it is acceptable not mandatory, and others asserting there is no direct call for genital cutting in the Quran. Rabiya made her case by invoking the complexity of the Quran, invoking a historical religious episode when the whole night was spent deciphering the meaning of a single letter in a surah. “If a single letter can have so many meanings, we can only imagine what this is about. A one liner cannot do it justice.”

This still didn’t answer the question of religious sanction, however. When pressed further, Rabiya said the community’s spiritual leader had spoken about the importance of the practice in very subtle but indirect ways. “The ones who want to take a message from it will do so. It also comes down to personal belief.”

Iqra*, a 38-year-old schoolteacher, also invoked God—but in a different sense. “I believe it is there for a reason,” she said, referring to the nick of skin that was taken from her. “God created it for a purpose. My circumcision was done merely for symbolic reasons, so the procedure did not have any severe implications in my life. Having said that, I am unaware of how much my sexual experience has been altered due to the obvious fact that I was not sexually active at age seven.”

SEVEN-YEAR-OLDLeena’s circumcision was not performed by a doctor. Her experience was typical: the woman administering the cut is often not medically trained, nor does she necessarily administer anaesthesia. Now, due to greater awareness of hygiene and health risks, healthcare providers are sometimes involved, carrying out the cut in sterile environments.

“We need to ensure communities are not unjustly profiled. But we also need to let FGC come into public dialogue. It is a difficult balance to maintain.”

This is known as medicalised female genital mutilation but some doctors, including Dr Ahsan, refuse to use the term. “I do not think any medical practitioner will agree unless they belong to the same community and hold the same religious beliefs,” she says. “Anything suggesting otherwise could be contentious because there are no medical guidelines supporting FGC.” WHO condemns female genital cutting as it violates medical ethics; the risks of the procedure outweigh any perceived benefits, and activists argue, medicalising it only perpetuates it as a practice.

In June 2016, The Economist published a controversial editorial, arguing that a blanket ban—by the UK government—had been unsuccessful for the past 30 years, so milder forms of FGC ought to be allowed under medical supervision. Survivors and activists were outraged at this harm-reduction approach, arguing that it diminished not only their struggle against secrecy and patriarchal norms but also dismissed the psychological harm caused by cutting. Most activists believe the term “light FGC” disrespects the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “It grants leeway for such cultural practices to thrive,” said Taher.

In April 2017, an Indian American doctor was charged and arrested for performing FGC on two seven-year-old girls at a medical clinic in Michigan. At the time, there was a federal ban on genital cutting in the US, in place since 1996, with the law amended in 2013 to outlaw taking a child abroad for circumcision. The Michigan case was significant in that it brought global attention to a neglected issue but exposed a dilemma: activists hailed efforts to hold offenders accountable, but others fretted it would be used against a vulnerable Muslim group at a time of heightened xenophobia. Yet others feared that it would cause the community to become even more secretive about the practice, further endangering young vulnerable girls.

On the contrary, it was one of the factors that compelled Leena to speak publicly about her experience.

“It is a global issue,” argued Taher. In India, where activism in the past five years has forced scrutiny on the practice, it emerged that genital cutting was being practiced in Kerala, and not just among Bohras. “We need to break stereotypes that it happens within only one community. We need to ensure communities are not unjustly profiled and made more vulnerable. But we also need to let FGC come into public dialogue. It is a difficult balance to maintain.”

Source: The Orchid Project

THERE MAY BEother communities in Pakistan that also practice female genital cutting. Sheedis, descendants of African slaves, sailors and merchants, based primarily in Sindh and Balochistan, are believed to carry out genital cutting, but there is little research to verify this.

Samina Hyder, a social worker in Badin, Sindh, has seen several documentaries about FGC within her community, but has yet to encounter a case in real life. Perhaps it is a thing of the past? “It is possible it happens in the Baloch community,” she said. “There is a lot of awareness and education here, which is why I think it has ended.”

Shama and her daughter Shehla agree with Samina: “We didn’t get our girls circumcised, nor were we circumcised by our mothers or grandmothers.” Sitting in the courtyard of their house in Lyari, surrounded by four excitable little girls, they didn’t recoil at such an invasive question.

LEENA’S HUSBAND DID not even know about female genital cutting until she confided in him. “He listened intently when I explained what I had gone through. He made a promise that he would never let our daughter go through the same thing.” It remains unclear whether Bohra men are in general aware of the practice; sexuality in general is a touchy topic across Pakistan.

“I am fairly certain the boys know this happens, but they choose not to interfere,” said 25-year-old Sabiha*. “There is a whole stigma around menstruation and other such ‘feminine’ issues. It’s just that such things aren’t discussed in Asian households. Elders consider it immodest.”

“Such decisions tend to be made by women in the family, who have themselves undergone genital cutting—something which still surprises Leena.”

“They are not bothered because they are not directly affected by it,” said Sumaira. According to 32-year-old Moiz*, however, it was only during his university days that he came to know of the practice. He is strongly opposed to it: “Anytime you take something away from someone at an age where they can’t give consent, it is wrong; it changes them permanently.” But although he and his sister have had arguments with their mother, the family elders continue to adhere to it.

On the whole, regardless of the extent to which men are aware, such decisions tend to be made by women in the family, who have themselves undergone genital cutting—something which still surprises Leena. Sabiha remembers confronting her grandmother about why she was ‘robbed of her right’ to make a choice. “Everyone else was doing it, we didn’t have a choice,” her nani replied. Agitated, Sabiha turned to her mother. “I did research, and realised there was no harm in it,” her mother answered, politely.

WHO has a term for this tendency: socially upheld behaviour. Some practices, researchers say, are carried out to solidify a community’s identity; according to anthropologist Bettina Shell-Duncan, female genital cutting is strongly associated with ethnicity, a proxy for shared norms concerning marriageability, puberty, and sexual control. The practice is a symbol of these norms, so whoever breaks the pattern is considered deviant. Excommunication is a very real possibility. In fact, the current generation’s more aware and liberal outlook “compels family elders to circumcise their daughters so they don’t fall into ‘loose’ groups,” says Sabiha. “They do not know what will happen if they stop following traditions.”

Leena agreed. “The community can hold you hostage if you allow them to. It’s actually your own decision on how much it matters to you. The more influential families end up doing a lot without being questioned. Some families, on the other hand, are very fearful because access to the community brings out a lot of benefits to them that would otherwise not be possible.”

Leena never confronted her family. “I am an adopted child and my adoptive family is very conservative. Having a conversation about this topic would have been futile because their worldview revolves around the community. They would always err on the side of caution.” She did confide in her biological mother, with whom she is very close, who told her she had tried and failed to protect her elder sister from being cut. “If my natural mother couldn’t protect my sister—who was living with her—how could she look out for me?”

STILL, SAYS LEENA,there has been progress. She moved to the US as an adult and noticed that there was far more vocal opposition within the diaspora. She wondered why this was the case.

There may be several reasons. For one, the threat of excommunication is arguably more potent in Pakistan. “In the US, they are part of the bigger Muslim community, not exclusively the Bohra community,” Leena said. Moreover, the community’s relatively small numbers in Pakistan—approximately 30,000, residing chiefly in Karachi—may also be a factor. In a sense, the individual comes to stand for the community. “Had the impact of rebelling against a particular practice been solely on that one person who decided to speak out, it would have been a lot easier than dealing with the rippling effect it has on the entire community otherwise.”

But the greatest impetus for change may come from within communities, as women become sufficiently empowered, and are able to protect their sisters, daughters and nieces.

Recourse to anti-cutting laws also matters. In the US, says Leena, there are options. “You can complain to your doctor or social worker. I think those protective mechanisms give a pause to the parents.” Mariya Taher, of Sahiyo, highlighted the role of political and cultural contexts. “In the US, there is greater freedom of speech. Survivors and activists are able to make themselves heard and get the attention of human rights groups.” The demographic diversity of the US means there are critics from within a multitude of communities, creating—literally—a critical mass. But the seriousness of the government in tackling gendered violence also matters: “This is exactly why Pakistan, India and the US are at different stages. But that we recognise this practice takes place globally is huge in itself. It shows the epic silence has finally been broken.”

Even within the US, though, there have been setbacks. In 2018, the Female Genital Mutilation Act 1996 was struck down by a federal district judge, who not only argued that it fell outside the jurisdiction of the federal government but also dropped charges against eight people who had cut the genitals of nine girls. The Department of Justice did not appeal the ruling, but the House of Representatives decided to do so. The motion, however, was denied. As of August 2019, 35 US states have made specific laws prohibiting female genital mutilation.

But the greatest impetus for change may come from within communities, as women become sufficiently aware and empowered, and are able to withstand pressure and protect their sisters, daughters and nieces. “As with all other things like globalisation, exposure to media, changing perceptions of sexuality and women’s rights, there has definitely been a change within the community all over the world—be it in India, Pakistan or the US,” said Leena.

She has decided she will not get her daughter cut. She does not fear excommunication.

She is not the only one planning on disrupting the cycle. “Many years later, I realised what had happened to me in my mid-teens. My body was used as an object against my will, to uphold an inhuman principle,” said Amna*, 27. “They tell us to bury the memories and to never speak up. But they should not forget what they did and continue to do to us. Because we will remember.” ■

A note on terminology: Female circumcision, female genital cutting and female genital mutilation are sometimes used interchangeably. Female circumcision, an older term, has been criticised for drawing a parallel with male circumcision, obfuscating two distinct practices. The UN, alongside many women’s health and human rights organisations, prefers the term ‘female genital mutilation.’ There is concern communities could find the term ‘mutilation’ demeaning or it could imply the procedure is performed maliciously. This story primarily uses the term female genital cutting.

HINA JAVEDis a producer at Soch Videos.

Visuals by MARIAM ALI.

Note: The bulk of reporting for this story was conducted two years ago.

*Some names have been changed to protect privacy.